Your musical life will be much easier if you look for systems and ways to organize large clumps of knowledge into more easily digestible forms. The idea of chord construction can be simply broken down into 3 groups of sound, each of which has its own subdivisions; these groups are based on three main chords: the MAJOR chord, the MINOR chord, and the DOMINANT

7th chord.

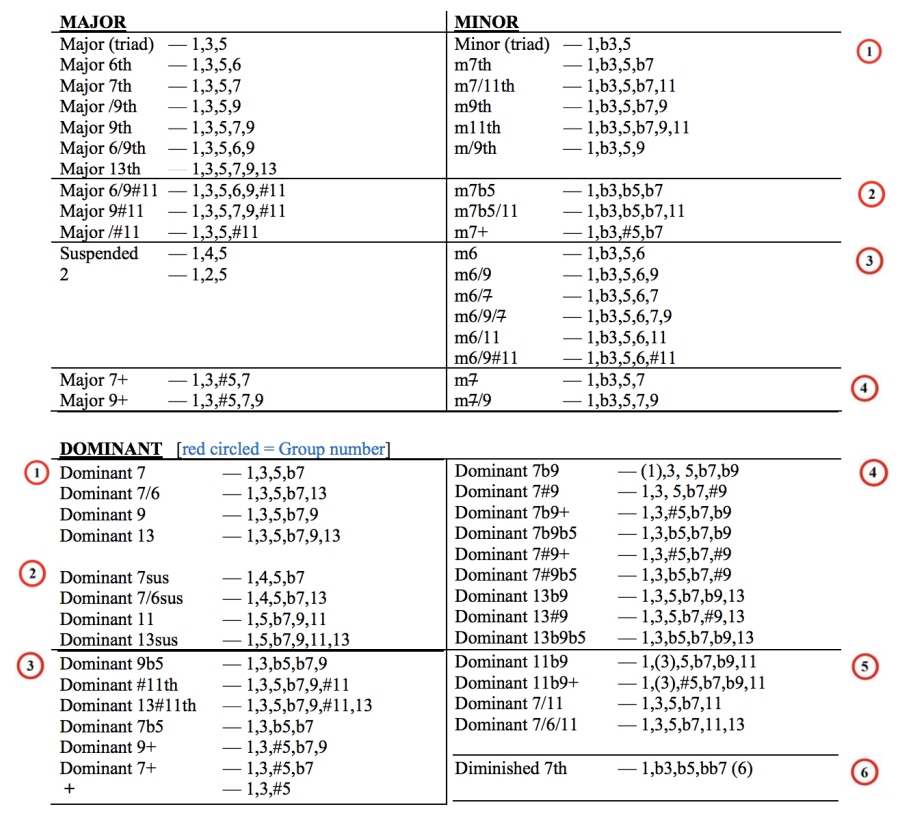

As you know by now, chord construction can be, and is most often viewed in relation to major scales. For instance, any major chord is built by combining the 1, 3, and 5 (Root, 3rd and 5th tones) of its own major scale — like a G major chord has the notes G, B, and D which are the 1, 3, and 5 of the G major scale. With this in mind, here is a listing of the most common chords in the three categories:

Don’t let this list frighten you. With patience you will know all these before too long.

The major, minor, and dominant 7th chords will be referred to as the parent chords of the three families of sound; all other chords are called extensions of these.

Not all notes need be played in most chords. Quite often, the 5th or root are left out; sometimes both; also the 3rd is omitted occasionally. However, rather than trying to build these chords on your own, you should save the time and energy by learning the chords that have already been worked out for you on the Essential Chords Lists and analyzing these chords to spot the above principles at work.

I. In theory, any extension in one of the three families above may replace its parent chord (like A∆7 or A∆13 for A) or (Am7 or Am6 for Am) etc. However, much experimentation and listening will be required to effectively utilize this concept and some general guidelines should help.

1) All the major extensions will pretty much fit as substitutes for any major triad that is not functioning as a dominant or dominant of a dominant (VofV, etc.). Another way of saying this is that the extensions all lie pretty well on I, IV (in major, not minor keys). bII, bIII, bVI, and bVII; also more rarely on bV. Some other major substitutes: a) /9, 2, on II, V, VI. b) sus on all degrees. c) 6 or 6/9 rarely on other degrees. Be careful with altered 5th or #11 type major chords; they are not as easily substituted as the others.

2) The minor extensions fall into four main groups as you can see [in Part 1].

Group 1 – can all usually be used to replace any minor or minor 7 chord.

Group 2 – are used to replace minor 7’s and are most common on ii of a minor key (vii of major).

Group 3 –

a) Used in place of i’s, iv’s, and bvi’s – like if you were given C E7 Am F G7 C, you could use Am6 or Am6/9 for Am because Am is functioning as i temporarily (remember those principles of tonicization?)

b) For an altered effect, this group also can replace dominant 7th types whose roots are 1/2 step lower (like Am6 for G#7)

c) Also, this group has the same notes as Group 2 chords whose roots are a m3rd lower – like Am6 = F#m7b5. These principles are only given to increase your awareness of inter-relationships. You will arrive at the same notes through other means that will be given.

d) Minor 6 and minor 6/11 chords are used on ii; Group 3 also works rarely on biii, vi, and bvii.

Group 4 – Are used most often in moving line progressions such as Am, Am∆7, Am7, Am6, or are used when the ∆7 is on top for the melody effect this creates. Your best bet to learn about these chords would be to eventually explore the following tunes: "Michelle", "My Funny Valentine", "More", "Embraceable You", "Taste of Honey", "Volare", "The Summer of ’42", "Something", and "Blue Skies".

3) The dominant 7th extensions are a truly vast world of sound, and because of the frequency of the V7 – I (i) progression in Western music, this compounds the issue even more. However, as mentioned before, systems can speed up the learning process considerably:

1) Group 1 consisting of 7/6, 9, 13 (and the 7th itself) have a “pretty sound” (these definitions are just one man’s opinion – make your own judgments also) on some degrees, and a “bluesy” or “modern” sound on others. Through trial and error you will determine on which degrees of the scale you favor these sounds. However, the top note (melody note) in these chords plays a big part in your ears’ acceptance or rejection of these sounds, so watch closely what is going on with the melody and listen.

2) Generally, wherever Group 1 works, Group 2 will also.

3) Group 3 is a unique group of sounds – all these sounds have a strong affinity to one of the two whole-tone scales and also to a melodic minor scale. There are different types of sound within this group: one type includes the + [augmented], 7+, 7b5, and 9+. This type can often be used to replace a dominant 7th functioning as a V7 (or V of V, etc.). The other type includes the 9b5, #11, 13#11, and 7b5 again. These all have notes which are within a melodic minor scale whose root is a 5th higher (like A13#11, #11, 9b5, 7b5 are in the E melodic minor scale). These chords work well on the following degrees:

On I – as ending chords

On bII as substitutes for V7

On II (in major keys usually) for II7

Occasionally for bIII (in major keys usually for VI7

On IV for IV7

On #IV (bV) for I7,

Rarely on V for V7

On bVI for II7 and bVI7

On bVII for II7 and bVII7

4) Group 4 are used to replace 7th’s functioning as V7’s.

5) Group 5 are used almost exclusively on V for V7 (also rarely on I, II for I7, II)

6) The diminished 7th will be discussed later. It is unique.

7) Group 1 chords (and occasionally Group 2) are commonly used to replace dominant 7th types whose roots are a b5th higher (like C7 for Gb7, C13 for Gb7).

8) Try ∆7+, ∆9+ for 7+ for an unusual quality; also m7+ for 7#9+.

Andy Martin is a guitarist from California whose instrumental compositions exhibit depth, taste and original expression with a wealth of harmonic content.

His latest CD is entitled "Brother From Another Mother", featuring his two-handed tapping technique.