One of the common threads that links almost all types of music that you might hear (like popular, jazz, classical, blues, rock, folk, etc.) is the concept of Tonality or Key. If you’ve ever played a song, classical piece or jammed on the blues, the chances are good that you were aware that it was in a certain key. But what does this mean, to be in a certain key or tonality? How does anybody know what key they’re in (“Hey Egbert, what key you in?” “Key of A, man, key of A.”)? It’s very hard to give simple answers to these questions, and the only way you’ll really understand what this is all about is to study music, to analyze music, and then the answers will appear.

But for now, so we have some working basis, let’s say that the concept of tonality or key has to do with the idea of one note or sound being the “center of attraction.”

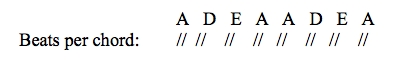

Example: Play this chord progression:

Can you hear that it is in the key of A major (key of A, for short)? Why is it in the key of A, and not D or E? Because the A major chord is the “center of attraction.”

If all examples were as easy to analyze as this (as far as finding the key), you wouldn’t have to do much studying. But unfortunately...

In case you are asking yourself at this point, “Do I really want to study all this just about tonalities and keys?” remember: Virtually all music as we now know it is based on the concept of tonality or key. If you want to be a musician, and you don’t want to study this concept, it is like wanting to be a farmer but not wanting to study agriculture - you might as well forget the whole thing - “you ain’t goin’ very far.”

But don’t worry, it won’t be too painful. Many have come this road before you and even lived to tell about it. So, here we go.

The Major Scale has been the foundation of musical theory in the Western world for hundreds of years. One who has a friendly, working relationship with the major scales will progress many, many times faster in some very important areas like chord building, chord progressions, and true musical understanding (the knowledge of what sounds work together, and why) than one who does not. Time and time again, I have seen this to be true; in fact, I personally tried to avoid learning about major scales, and I floundered for years, especially in the area of retention (the long-term ability to remember). So many facts seemed unrelated or would slip away too easily because there was no common thread (namely, the major scale) to tie them all together. But all that has changed now – things make sense, there is order, there is logic, much of the seeming complexities of music can be easily understood, but you have to have a good foundation to build on.

So now you might be asking, “What is a major scale?” or “What is a scale?” for that matter. OK. A Scale is a fixed group of notes, almost always constructed in an ascending direction, from a given starting note.

Before we can discuss the major scale in more detail, we must first talk about intervals. The word Interval,i in music, refers to the distance between any 2 notes. Two of the most basic kinds of intervals are the 1/2 step and the whole step. The term 1/2 step refers to the interval between 2 notes that are adjacent (right next to each other) in the musical alphabet. Examples: A and Bb, Bb and B, B and C, C and C#, etc.

(If you are at all shaky on your musical alphabet, there are 4 easy drills that will sink it in fast - ask for them if necessary). Back to intervals.

The term whole-step refers to the interval between any 2 notes that are separated by one note in the musical alphabet. Examples: A and B, Bb and C, B and C#, C and D, etc.

So how does all this relate to the major scale? I will shortly explain this, but first, re-read any point that is not absolutely clear, or you might get lost as we move forward.

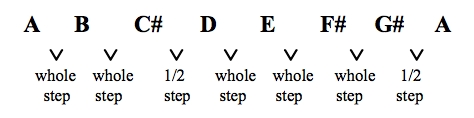

A major scale has, starting from any note, the following intervals between its successive notes: Whole step, whole step, 1/2 step, whole step, whole step, whole step, 1/2 step.

Example: starting from A:

Notice that the notes C#, F# and G# were used rather than Db, Gb and Ab. These is a good reason for this, but it’s too complicated for now, but the following guideline will produce good results at this stage of the game: All letters of the musical alphabet must be present in a major scale.

Write out the notes in the D major scale.

Write out the notes in the Bb major scale.

(A fast way to write out a major scale it to write out the “bare” letters first - that is, with no sharps and flats - and then add the necessary sharps and flats).

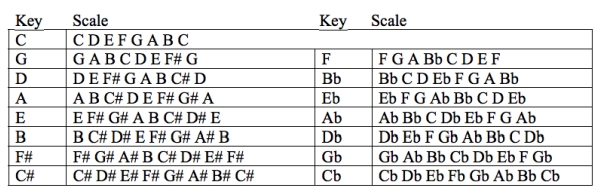

Here is a listing of the common major scales (some are admittedly less common than others). Make it a point to mentally memorize (physically too - this will be discussed soon) at least one scale per week.

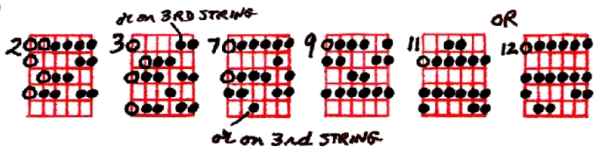

Depending on what direction(s) you want to go in, musically, you will find it very important (to mildly important), to be able to fluidly play the major scales. Here are some common diagrams (given in the key of D only):

As far as emphasis goes, remember your goals - is a command of the major scale necessary (let’s discuss it again if you’re in doubt as far as your priorities go)?

1) First of all, in case you’re not aware of it: Every scale has chords inherent in it, or to put it another way: You can build chords from any scale. How? Well, to start with, the 1st chord in a scale is built by combining every-other note (non-adjacent notes) in the scale, starting with the 1st note.

Example: Using the D major scale, we will combine every-other note in the scale, starting with the D note, and stopping after 3 notes are combined, for now. Result: we would have a chord consisting of the notes D, F# and A. Three-note chords built in this fashion are called Triads.

2) Triads can also be built by combining every-other note in a scale but starting from other notes than the 1st one.

Example: In the D major scale you also have the following triads: E G B, F# A C#, G B D, A C# E, B D F#, and C# E G.

Don’t go any further if all this is not perfectly clear. Reread whatever you have to and/or ask questions.

In order to be able to name the triads in a major scale, we have to talk a little more about intervals.

Important: most intervals are classified according to at least 2 characteristics:

1) Their general name, which is found by counting up the alphabet and adding up the number of letters included.

Examples:

C to F is a 4th (because there are 4 letters included Æ C, D, E, F),

C to F# is still a 4th (#’s or b’s don’t matter in the general name),

A to G is a 7th, F to D is a 6th, F# to C is a 5th, Gb to C is a 4th, and so on.

2) Their specific name, which is found by counting the number of whole steps or 1/2 steps between the notes (there is also another method used to find specific names, and it will be discussed later).

Before you work with examples of this principle, the following should be said: Triads are built in 3rd intervals. One definition of a triad then is: A 3-note chord built in 3rds. (Notice the term “3rds” used for the term “3rd intervals” — this kind of slang is common).

Go back and check those triads in the key of D now, and see if you think they are built in 3rds.

Now for the specific names — there are two types of 3rd intervals in all of the commonly used triads, namely, the Major 3rd and the Minor 3rd. (The major and minor are the specific names.) What is the difference between the two? It’s in the number of whole or 1/2 steps involved:

1) A Major 3rd has 2 whole steps between the 2 notes involved.

Examples: A to C#, B to D#, C to E, Db to F, D to F#, etc.

2) A Minor 3rd has a step and a half (one whole step and one 1/2 step) between its notes.

Examples: A to C, B to D, C to Eb, Db to Fb

(notice that Db to E would be a 2nd interval, not a 3rd)

D to F, Eb to Gb, F to Ab, G# to B, etc.

Stop now, and reread anything that is not clear to you before you forge on.

There are 4 types of common triads, all of which are distinguished from each other by the types of 3rd intervals used in their construction:

1) The Major Triad has the following intervals (from the bottom up): a major 3rd and a minor 3rd.

Example: a D major triad has the notes D, F#, A

(D to F# is a major 3rd, and F# to A is a minor 3rd).

Another example: An Ab major triad has the notes Ab, C, Eb

(Ab to C is a major 3rd, and C to Eb is a minor 3rd).

2) The Minor Triad has the following intervals (from the bottom up): a minor 3rd and a major 3rd.

Examples: a D minor triad has the notes D, F, A;

an F minor triad has the notes F, Ab, C;

a B minor triad has the notes B, D, F#.

3) The Diminished Triad has the following intervals (from the bottom up): a minor 3rd and a minor 3rd.

Examples: a D diminished triad has the notes D, F, Ab;

an F diminished triad has the notes F, Ab, Cb;

a B diminished triad has the notes B, D, F.

4) The Augmented Triad has the following intervals (from the bottom up): a major 3rd and a major 3rd.

Examples: a D augmented triad has the notes D, F#, A#;

an Ab augmented triad has the notes Ab, C, E;

an F# augmented triad has the notes F#, A#, Cx (double sharp)

There are common symbols used to identify the different triads:

1) A major triad is written without any symbol other than the letter name itself. Example: if you see a chord diagram labeled D, it is understood that this is supposed to mean a D major chord.

2) A minor triad is symbolized by a small “m” or the word “min.” Example: Am or Amin.

3) A diminished triad is symbolized by a little o. Examples: Co, Bo, Go, etc.

4) An augmented triad is symbolized by a little +. Examples: C+, B+, G+, etc.

Stop now and review anything that is at all fuzzy. (You are not expected to have all this information memorized now, but you should at least understand it before moving on).

Andy Martin is a guitarist from California whose instrumental compositions exhibit depth, taste and original expression with a wealth of harmonic content.

His latest CD is entitled "Brother From Another Mother", featuring his two-handed tapping technique.